A History of Finnish Shamanism, Part 4: A Shamanic Healing

Introduction

I am diverging from my planned order of posts of A History of Finnish Shamanism to take a turn to the personal. In the present post I describe a shamanic healing session held for me near Helsinki several years ago by Johannes Setälä and Susanna Lendiera, who practice in the joint noita/tietäjä tradition of Finland and Karelia. In recounting my experience, I explore the nature of shamanic healing in this tradition and conclude by explaining why I believe it has a special role to play in supporting us, both individually and collectively, as we confront urgent threats to the future of the animist lifeworld.

My Healing Session

I am using terms for the healing ritual that derive from the ancient traditions of Finland and Karelia, that I will introduce and explain based on my understanding of them.

My session with Johannes and Susanna consisted of drumming and chanting and the invocation of a series of subjects of mythic images, some of which are pictured below.

As the session progressed, I was elevated to the heights of the mythic World Tree and later taken underground, where a sacred cliff with rock paintings was tilted and placed over me. Susanna called upon snakes as spirit helpers in her soul journey to assist with the ‘heavy lifting’ that she later said was required in my case.

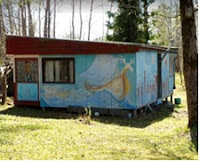

The ritual took place in a dedicated ceremonial space made sacred by paintings by Johannes and power objects he has collected, and by its location on a previous dwelling site of Neolithic hunter-gatherers.

Luonto

I will suggest

below that the healing session strengthened aspects of my luonto,

or personal ‘nature’. Luonto is a

form of väki, a supranormal energy or force possessed by various

entities of the world, including persons, objects, and natural elements.

In humans, the väki

force energetically ‘imprints’ the essence or ‘personal nature’ of the person

that underlies their agency to influence the world, or what Comparetti calls

the “productive genius of the individual”.

Luonto, or personal nature, is continuous with

nature as a whole and can be summoned or raised from the earth itself. A common incantation for this purpose says,

“Rise, my luonto, from the lovi (i.e., a cleft or hole in the

earth), my haltija from the undergrowth”. When one’s luonto force is raised

quickly and vigorously enough, the person can enter an ‘ecstatic’ or trance

state. In fact, Siikala says that among

other terms for being in a trance state in Finnish is to be “in one’s luonto (=

in an ecstatic state)”.

Haltija

I was accompanied

in the session by my haltija, my spirit guardian, who played an

important part that I will explain below. The haltija is the ‘face’ or

personification of a person’s luonto energy body in the other world—its

avatar. Tolley says in shamanistic times, it must have been an “independent

assistant spirit” of the shaman.

Vilkuna says,

“every full-fledged human being has his or her own haltija”. In fact,

“Only when it has entered the person after birth does the person concerned

become a real person".

|

| Cuckoo (Kuukkeli) |

The form of one’s haltija is not fixed and can manifest, for example, as a bird, bear, a human person, or any other conceivable being. My own spirit guardian takes the form of a Eurasian elk, alces alces, known as moose in North America.

More or less independent of the body, the human haltija is sometimes called “shadow-haltija” (varjohaltija), closely accompanying a person (as a shadow) while guarding and protecting them.

|

| Tero Porthan, Deviant Art |

Speaking of

pre-modern Finland, Siikala says, “At times, the link between persons and their

guardian spirits was seen to be so close that the concept of ‘guardians’ could

take on aspects of ‘soul’ or ‘soul portion’”.

The haltija of a human is the counterpart of the spirit guardian, haltija, possessed by phenomena of nature, including animals, birds, fish, and plants, as well as natural places and physical formations. As well, many phenomena of social life, such as beginning in the Iron Age, of buildings and farms, possess them. I will explore the haltija of animals in a later post, as the spirit guardians of game species are key to understanding the animal ceremonialism that ensured the survival of foragers.

When elements of one’s luonto-force

are blocked or impeded through physical illness or life circumstances, as

happened in my case, they become ‘weak’ or ‘soft’, and a person cannot fully

exercise their own unique powers. However, one’s luonto can be

strengthened through ritual means. One

practice is luonnonpalautus, or ‘restoration of the nature’, the luonto. Another related healing practice known across

shamanic hunting cultures was the recovery of a haltija that had become

strayed or lost.

A serious condition is that of soul loss, when

one’s free soul wanders or is lost in the lower world. In this case the appropriate form of shamanic

healing is ‘soul retrieval’ (in Finnish, sielunpalautus,‘restoration of

the soul’). Ingold says, “shamans of

animic society make their often arduous journeys to the communities of

non-human animals is to recover vitality that may have been lost, due to some

untoward circumstance, to the ‘other side’. Such loss is generally experienced

in the form of serious illness, and by bringing vitality back to the sufferer

the shaman aims to effect a cure”.

Noita and Tietäjä

For healing ceremonies, the shaman, noita

in Finnish, uses a heightened energetic state to ‘become’ or ‘enter’ their

‘free soul’ or ‘shadow soul’, in Finnish itse, that can engage in soul

journeys to the other world accompanied by their haltijas and other spirit

helpers. While in the other world they directly interact with beings

there and solicit their active assistance for healing purposes. (Itse is the free or ‘mobile’ soul,

while löyly, that today also means ‘sauna steam’, is an ancient term that refers to

the breath or body soul--the life force—that departs at death.)

I will argue in upcoming posts that the shaman was the main healing practitioner in Finland and Karelia from the Mesolithic through the Bronze Ages. Beginning in the Iron Age, with the development of agriculture, tietäjäs emerged as a new type of healing practitioner.

A principal difference in practices between the two types of practitioners--tietäjäs and noitas--is that tietäjäs typically ‘remotely’ activated the powers of the other world, that is, without entering the free soul to journey there and directly communicate with its beings, as noitas had done. They did this through performing—in an ‘ecstatic’ state, i.e., with raised luonto—incantations composed of specially tailored combinations of images from the Kalevala runic tradition that addressed the synty, the ‘birth’ or origin, of an individual’s particular illness or energetic intrusion. Properly delivered, the incantation, as an animate sacred artwork, had independent effectivity in banishing or otherwise neutralising it.

In his writings, Mr. Frog has extensively explored

differences between the two types of practitioners.

|

| © Johannes Setälä |

Pictured above is an exemplary tietäjä who also maintained core elements of the earlier noita institution in his practice. He is Miines “Miina” Huovinen, (1837-1913), from Hietajarvi, Archangel Karelia. He was known for his exceptional ability in healing that he had learned from his grandmother Toarie.

Another exemplary tietäjä was Marina Takalo, (1890-1970), born at Oulanka near Kuusamo, Finland. She was a highly accomplished rune singer (runonlaulaja), as well as a tietäjä and a seer (näkijä). Susanna considers her a noita as well.

Marina Takalo is shown above near her birthplace of Oulanka, at the red ‘power stone’ cliffs of the Kiutaköngäs Rapids of the Oulanka River.

Johannes and Susanna practice in the joint noita/tietäjä tradition. They and many others are helping maintain it as a living tradition in Finland, to which I applied my own term in an earlier post: ‘Kalevala-era shamanism’. Presently, Susanna is primarily concentrating on honouring the tradition through her art and photography.

Returning to the Ceremony

In my healing session with Johannes and Susanna, the chanting and drumming raised my luonto and I entered my itse, my ‘free soul’ or ‘shadow soul’ and began journeying. Click below for an audio excerpt from the session.

Comparing my experience with Susanna’s later description of the session, I was surprised that while there were differences, her description and my own experience were quite synchronous in what I ‘saw’ and ‘felt’ as it unfolded.

For example, in the session, I was taken to the top of the World Tree, that focussed the mythic powers of growth and renewal of the tree to raise my life force, my löyly, empowering me to stand straight and tall like the tree itself and to accept myself in this way. At the same time as this was happening, I was experiencing travelling with my haltija high in the sky, feeling the exhilaration at looking through shimmering leaves and seeing a tree far below, as in the above photo.

At another point I experienced the heavy, intense feeling of being underground as I and my haltija went to the roots of my familial namesake tree, the alder or leppä, a species that is associated with the lower world.

As part of the session, I was also being taken underground, but now the cliff with rock paintings was being placed over me. This exposed me in a visceral way to the concentrated healing and other powers of the sacred living artworks and bonded me with the ancestral shamanic tradition out of which the paintings arose.

I made gains from the session that have lasted over time. From my perspective, the ‘heavy lifting’ on the part of Susanna and Johannes and their spirit helpers made available to me forces and powers from our shared mythic tradition, helping to revise and revitalise aspects of the energetic imprint of my individual ‘nature’.

Energising the Animist Lifeworld

Luonto and similar dynamic forces, for example, náttúrá

of the Old Norse and the Viking concept of meginn,

were known across the pan-Scandinavian, post-shamanic cultural

context. Similarly, the word haltija

is of early Germanic origin.

As we have seen,

Tolley, through his extensive study of the shamanism of the Nordic region,

considers that both luonto and haltija to date back to shamanism.

I would argue

because of the probable roots of luonto/haltija in the

institution of shamanism and given the fact that their basis is the ancient

Finno-Ugric energetic principle of väki, we can compare them with

similar examples of dynamic forces in the earlier shamanic archaeological

cultures in the Uralic and near-Uralic area.

These include the oni, or life force, and onnir, or ‘spirit charge’ of the Evenki, a Siberian

people whose shamanic practices that are closely related to those of Uralians, and,

according to Siikala, were particularly close to those of wilderness

Finns.

We can also include Hamayon’s description, from his

study of Siberian shamanic peoples, of a transferable ‘life force’ shared between and among

species and the reincarnation of souls of animals that is at the basis of

animal ceremonialism. He says, “Life

force is a substance that may vary in quantity and quality during the lifetime

and circulates between species to keep them living and animated…. By

contrast, the soul is an individual entity held to survive after death and then

be reborn for a new life strictly within the same human line or animal

species”.

Another type of dynamic force is what Zagorska identifies as a “magical force” inherent in red ochre that assists souls to travel to the other world. She is referring to the iron oxide-infused clay, reminiscent of the colour of blood, that is widely used in Mesolithic and Neolithic burials. The photo below from the National Museum of Finland shows a burial site from the Mesolithic Suomusjärvi archaeological culture, with red ochre sprinkled in a grave.

What the above types

of dynamic forces have in common is that they vivify or energise the

animist lifeworld. As such, they

find a place as part of Ingold’s umbrella concept of ‘vital force’ circulating

throughout the animist lifeworld, that he says is “often envisaged as one or several

kinds of spirit or soul”.

In view of the

pervasive nature of these circulating energetic forces and the integral,

interdependent, nature of the animist lifeworld, it is not surprising that

foragers, through their mythical

consciousness, grasped that the

lifeworld itself is independently alive.

According to Anisimov, “the

materials on the ethnography of the peoples of Siberia show that the universe

itself was conceived of as a living being and was identified with images of

animals in the concepts concerning it”.

Freeing Vital Force

Based on the above, I suggest my own healing experience can be seen as an intervention in a moment of obstruction or other diminution of the circulation of vital or soul force, in this case in human persons.

Shamanic healing rituals are not therapy or treatment in the modern sense, in which individuals are the only beneficiaries. For example, if we look back to a band of Neolithic foragers, it required that vital force flow as freely as possible through the bodies and lives of all its members to align their unique powers with those of the animist lifeworld. This made it possible for members to fully exercise these powers, safeguarding their own survival and well-being, and thereby that of the entire band, in the challenging forest environments in which they lived. Healing rituals by shamans and spirit helpers were undertaken when the force did not freely flow in this way.

In the session conducted for me, Susanna, Johannes, and their spirit helpers ‘saw’ blockages in the flow of vital force in me and invoked mythic sources of healing to help remove them. As a result, I feel my capacity for agency as a person and as a shamanic practitioner was enhanced. I believe that this parallels the situation of wilderness foragers in that today, the unique powers of all of us are needed to confront the challenge of a planet on life support. Shamanic means of healing—in tune with the nature of the animist lifeworld and connecting us with its mythic powers—have much to offer in this regard. Susanna as quoted in an earlier post, has said, “Our species is destroying mother earth. We need to reconnect with the ancient wisdom tradition that promotes harmony with the natural world. It is our responsibility to future generations”.

Works Cited

1. Siikala, Anna-Leena. Mythic Images and Shamanism: A Perspective on Kalevala Poetry. Helsinki : Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2002.

2.

Comparetti, Domenico. The traditional poetry of the Finns. London :

Longmans, Green, 1898.

3.

Tolley, Clive. Shamanism in Norse Myth and Magic. Helsinki :

Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2009.

4. Vilkuna, Asko. Uber den finnischen haltija, Geist,

Schutzgeist. [book auth.] Ake Hultkrantz. Supernatural Owners of Nature:

Symposium Papers. Stockholm : Almqvist & Wiksell

International, 1961.

5. Pulkinen, Risto, Lindfors, Stina. Suomalaisen

kansanuskon sanakirja. Tallinn : Tekijat and Gaudeamus, 2016.

6.

Ingold, Timothy. Totemism, animism and the depiction of animals. The Perception

of the Environment. London and New York : : Routledge, 2000.

7.

Pentikainen, Juha, The Human Life Cycle and Annual Rhythm of Nature..

Helsinki : Finnish Society for the Study of Comparative Religion, 1985,

Temenos, Vol. 21.

8.

Frog. Ethnocultural Substratum: Its Potential as a Tool for Lateral Approaches

to Tradition History. Helsinki : University of Helsinki, 2011, The

Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, Vol. 3.

9.

Stark-Arola, Laura. Magic, Body and Social Order. Helsinki : SKS, The

Finnish Literary Society, 1998.

10. Vilkuna, Asko. Das Verhalten der Finnen in

"Heiligen" (Pyha) Situationen. Helsinki : Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1956.

11.

Lavrillier, Alexandra. Lavrillier, A. (2012). 'Spirit-charged' animals in

Siberia a (pp. 113-129). New York: Ber. [book auth.] V.E. Grotti, O.

Ulturgasheva M. Brightman. Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood,

animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia. New

York : Berghahn Books, 2012.

12.

Hamayon, Roberte. Shamanism and the Hunters of the Siberian Forest: Soul,

Life-force, Spirit, Roberte Hamayon. [book auth.] Graham Harvey. The Handbook

of Contemporary Animism. London : Routledge, 2015.

13.

Zagorska, Ilga. The Use of Ochre in Stone Age Burials of the East Baltic. [book

auth.] Fredrik, Oestigaard, Terje Fahlander. The Materiality of Death: Bodies,

Bburials, Beliefs. Oxford : Archaeopress, 2008.

14.

Anisimov, A.F. Cosmological Concepts of the Peoples of the North. [book auth.]

Henry N. Michael. Studies in Siberian Shamanism. Toronto : University of

Toronto Press, 1963.

15.

Ashihmina, Lidija I. The Importance of the Moose to the People in the Northern

Sub-Urals During the Bronze and Early Iron Ages. 2002, Alces: A Journal Devoted

to the Biology and Management of Moose , Vol. Supplement 2.

16.

Frog. Do You See What I See? The Mythic Landscape in the Immediate World. Tartu :

Folklore , 2009, Folklore, Vol. 43.

17.

Frog. Ethnocultural Substratum: Its Potential as a Tool for Lateral Approaches

to Tradition History. 3, s.l. : Folklore Studies / Dept. of Philosophy,

History, Culture and Art Studies, University of Helsinki, December 2012, RMN

Newsletter:.

No comments:

Post a Comment